Story by Somira Sao

It was early morning aboard Anasazi Girl. As I exhaled, I could see my breath curl like smoke through the cold air. I was lying with our three children in the starboard quarter berth. James sat at the navigation station, looking at our latest GRIB file, updating charts, and watching the boat’s performance. I could hear the sound of the ocean through the carbon hull as the boat surfed through the water.

I craned my neck so I could peek at the instruments. Then I carefully shifted my weight so I could crawl out of the berth without waking anyone. Getting out of a space intended for one person, then stepping out over the ballast plumbing was tricky. Gravity was pushing us to the lowest side of the berth, matching our angle of heel, with me at the bottom of the kid pile. The arrangement was uncomfortable, but it was the safest place to be on the boat. My intense love for my kids and the happiness felt having them close always worked to counter-balance any discomfort.

It was February 2014 and we were starting day 5 of our passage out of Auckland. With 60 days of provisions on board, our plan was to sail non-stop to Lorient, France. This was the first offshore passage for our one-year-old daughter Pearl. With many ocean miles under their belts, our daughter Tormentina (age 5) and son Raivo (age 3) were now well-seasoned sailors. If we made it to Lorient, it would complete an east-bound family circumnavigation via the three Great Capes.

We were trying to maintain a maximum boat speed of 10-12 knots while staying on an efficient and comfortable East-bound course toward the Drake. For this section of the Southern Ocean, the plan was simple – sail fast, sail smart, keep the lows on starboard, the highs on port, and above all else, do not get hurt or break anything!

As our position shifted southeast in latitude, we left our previous lives & the warm temperatures of New Zealand further behind. We had arrived in Auckland 14 months prior, in October 2012, after sailing from Cape Town, Fremantle, and Melbourne while I was pregnant. Our time in New Zealand had been quite special. For James and I, the place held a lot of personal history for us, going back before we had kids.

In 2007, James and I sailed Anasazi Girl across Cook Strait from Nelson to Wellington, then along the east coast of North Island from Wellington to Tauranga. We spent several months in Auckland, working on the boat in the Viaduct, on the hard stand by the old America’s Cup sheds on Halsey Street. James was preparing for a non-stop Eastward passage from Auckland to Cape Town and it was during this period that we decided to start a family and conceived our first child Tormentina.

This recent stop in New Zealand, we had given birth to our third child and I finally said “Yes” seven years after he asked me to marry him. We got married with a simple civil ceremony and celebrated with a memorable party afterwards.

Our kids ran wild & barefoot, tearing it up on the waterfront, wharfs, and docks on scooters and skateboards. We taught our kids how to swim at the Tepid Baths and lived a completely pedestrian lifestyle.

We made deep connections with friends, both old and new and enjoyed the beautiful sailing of the Hauraki Gulf. We also experienced America’s Cup madness as we watched the launch and sea trials of the AC72s in our “backyard.” We cheered on Emirates Team New Zealand with the Kiwis for the very dramatic 34th edition.

All of these things made our departure one of the hardest goodbyes ever leaving port. With the addition of one more crew-member, we cleared out of the country. Freed from the land, we were excited about making an epic voyage, and eager to see what would come next for our family.

Amazingly, we were in motion again.

I got up slowly, stabilizing my body against the starboard ballast tank and the navigation seat. Before I did anything – walk through the cabin, use the toilet, or put a pitcher on the stove to heat water – I sat down next to James to see where we were and what kind of conditions we were sailing. Sea state determines what we can and can’t do underway. In this case, we had stable NW breeze, were making good Easting, and seas were moderate. We were just over a thousand miles out of New Zealand. The forecast showed that we would get a SW wind shift in 4-6 hours. Right now, it was safe to be active and get some things done inside the cabin.

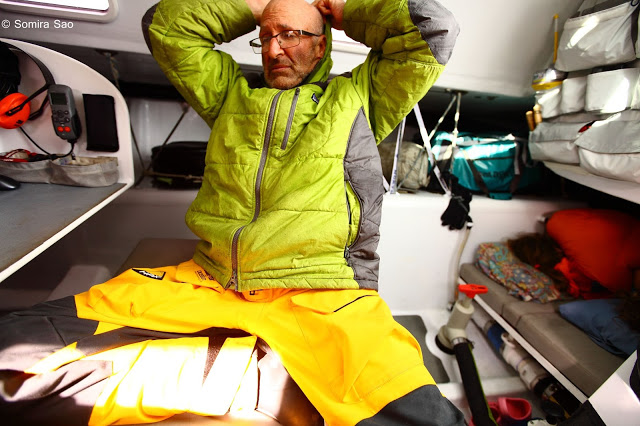

We commented on the temperature drop and discussed turning on the Eberspächer heater for the first time. It would instantly take off the edge until the sun warmed the boat, but we decided to wait. The kids were asleep, warm inside the cocoon of a giant down sleeping bag. In the meantime, hot drinks and staying layered in technical clothing would do the trick for the two of us.

We left port with 53 gallons of diesel and were guarding our fuel, which we needed to run the heater and the engine-driven alternator that charged our house batteries. Using minimal fuel was critical for keeping all our electronics running. Careful conservation of all our resources on board while simultaneously not carrying too little or too much of anything was a key factor for successfully making all our long distance passages.

Sailing offshore often pulls forgotten memories to the surface for me. Seeing our breaths as we spoke and our cups of tea steaming, I was brought far away from Anasazi Girl and back in time to our lives three years prior.

In March 2011, we were living in South America in a Peugeot Boxer cargo van (fitted out with a living interior) with our two oldest kids Tormentina and Raivo (ages 2 ½ and 6 months at the time).

At that time, we had just fulfilled a dream project of making an unsupported descent of Argentina’s Rio Santa Cruz with the kids. The seeds for this dream were planted with a Google Earth map and a few trips over the river on the Charles Fuhr Bridge (Ruta 40) while were cycle touring this region.

The river was an other-worldly blue, fed by the glacial melt of the Patagonian Ice cap and ran 400 kms from Lago Argentino to the Atlantic. The float was in a 15 foot hard shell canoe and lasted nine days. Alone in the wilderness, with very remote road access, we drank pure unfiltered water and passed landscapes of wind-blown pampas, abandoned estancias, basalt rock formations, saw guanaco & condor, and found Tehuelche artifacts.

After floating the Santa Cruz, we lived between southern Argentina and Chile so I could work shooting images. We spent time at the crag with an international tribe of climbers. That season, we met and re-connected with world-class athletes – like Rolando Garibotti, Sean Villanueva-O’Driscoll, Nico Favresse, Joel Kauffman, Daniel Jung, Sylvia Vidal, Tommy Caldwell, and the Huber Brothers.

We took road trips along desolate dirt roads, James always with one eye searching for undeveloped climbing areas and hidden crags of granite among thousands of sheep and the lone gauchos.

We eventually made our way south to the “end of the road” of Tierra de Fuego, to the port of Ushuaia, Argentina. The season was winding down and James found day work on foreign flagged expedition boats chartering Cape Horn & Antarctica.

We lived in the van at the yacht club, urban camping, paying for the use of the club’s facilities.

Then the first freezing cold nights arrived.

We slept layered in all our technical gear, surrounded in the morning by a cave of frost, breaths visible in the cold air. By the second morning like this, we knew it was time to head north.

This moment was a major turning point for us. As a family, life together was not about an existence of just living & working in a place. Neither was it just about being a tourist having a look around. What drove us to live was to go somewhere to DO something, to make friendships and deep human connections.

Always we strove to keep a healthy balance between working enough to live a simple life, while doing it in such a way that allowed us to be together as a family, to raise & teach our kids ourselves.

At this point, the river project was over, our tribe had left Patagonia with the seasonal shift, and we were burned out on being on the road. It was hard for us to be around the expedition boats without the freedom to be on the water ourselves.

It was time to start a new life program.

We headed north & returned to El Chalten to store our canoe & river gear at Alejandro Capparo’s house (the head park ranger at Parque Nacional Los Glaciares).

A couple weeks later we were in the big city of Santiago, camped out at the Herrara-Bravo house, trying to sell the van. Once we found a buyer, we then moved into a small room at the Hotel Paris, located in the old cobble-stoned Iglesia San Francisco district of Santiago. We then sold everything else we owned (climbing & camping gear) to the young Chilean climbers.

We booked tickets to Panama and spent a week there looking for work.

Two weeks after that, we were in Maine, preparing to re-launch Anasazi Girl. By the middle of July 2011 we made our first offshore passage with the family, crossing the Atlantic in 21 days from Maine to France. Three years and three children later, we had made over 20,000 ocean miles together, crossed the North & South Atlantic, the equator, and made East-bound voyages through the Southern Ocean to the point where we were today.

I felt a little choked up with the realization of how far we had come as a family since planning & provisioning for our small trip on the river. It had been a good exercise in risk management and expedition planning that helped shape the voyages we were to later make.

I thought about how those frosty mornings in the van had become such a pivotal moment in the course of our lives, and here we were again, about to cross that region where the idea to go sailing with the family had started.

We did turn the heat on that day, and the days that followed fell into a steady routine. These were not the sunny, warm days of sitting in the cockpit with the kids, making sail changes together, and watching for dolphins, birds, and whales like in the Atlantic. The Southern Ocean was a completely different game altogether. This type of sailing was an intensive risk management program where being smart was vital for everyone’s safety and even the smallest actions of everyone aboard were carefully calculated.

The kids understood that we were safest down below and when conditions were aggressive, it was best to be in the quarter berths. James was sailing single-handed. He made all sail changes on deck, examined lines to make sure there was no chafing, checked the condition of sails, lines & hardware, and obsessively checked and re-checked all our systems. On deck he always stayed clipped in and wore a safety harness with a built in PFD.

All of our senses grow more acute offshore, especially hearing, as we are always listening for good and bad sounds. Good sounds were his footsteps above us, sails getting dragged to the fore-deck or getting dropped down through the hatch, the winch handle locking in place, the subsequent grinding as the lines are adjusted or tightened, the click of the mast cars working as the main gets reefed or raised, head-sails getting furled or unrolled, and sails getting tightened or eased. Bad sounds were that of a sail or lines slapping loudly, loud bangs, or complete silence. By listening carefully and sensing changes in the boat, sails could be correctly adjusted for best performance.

All sail changes at this latitude were difficult, but a gybe always required special mental preparation. Gybes were few and far between, with an average of one gybe every 1000 miles. First we had to make the ballast adjustment down below. The kids would help us with the system of valves and scoops, which needed to be opened and closed in a specific order. They would watch the bright orange balls inside our sight tubes to let us know when tanks were empty or full.

Then James went through a meticulous process of putting on his “action suit.” Paying attention to the smallest details in his preparation to put on foul-weather gear and safety equipment prevented the possibility of tripping, base-layers getting wet, harness failure, a carabineer not getting properly locked, a head-lamp flying off, or a hood obscuring his vision. All of these things could cause stress, exhaustion, or mistakes, and we were in the business of taking extra care to avoid all of these possibilities.

Out on deck, James took calculated steps to make sure our gybe was a smooth & quiet transition. Once he stepped out, we prepared for the sound of sails getting reefed, lines getting adjusted and stacked neatly, the slide of the track as the boom shifted to the opposite side of the boat, an “OK” call from above, then sails filling, reef shaken, and lines tightened. Our bodies braced down below for the change in the angle of heel on the boat until sails and ballast were adjusted once again for comfort.

Down below my primary responsibility was keeping the kids safe. All physical movement was always very controlled. Even for our older children to use the head or move about the cabin required direct supervision. My eyes were constantly on them and on the instruments, watching for imminent or unexpected changes in wind speed or direction. If the kids were all asleep and tucked in safely, then James and I could sometimes make a coordinated effort to make a sail change, with me driving the boat down below with the autopilot and him on deck above.

Twice a day, we ran the Yanmar for 1-2 hours to charge the house batteries. Inside the uninsulated carbon structure, it was always a loud exercise, especially with the engine room doors open for good ventilation and easily accessible for inspection. During this time, we did all our power-intensive tasks: ran the water-maker, booted up the computer to update our position, downloaded new weather files and SAT-C (Navtex) warnings, downloaded & backed up image files, and charged the kids’ tablets. Once this was done, we allowed the kids to watch one movie on the big screen of the boat computer.

In the quieter times or during rough conditions, we took turns sleeping, reading or telling the kids stories. The kids played games or watched movies on their iPads. When things were stable, we would do an art project together, stretch, play music or have a dance party. Then there was the regular business of cooking, cleaning, drying out the boat, and maintaining everyone’s hygiene. Running the heat with little ventilation meant constant condensation, so it was an ongoing task to keep things dry inside. There was a constant rotation of squabs and sleeping bags hung up by the heater to get dried out.

For this passage with a crew of five and the kids eating more than ever, we provisioned partially with freeze-dried meals. When we were tired, it was a quick way of getting a balanced shot of nutrition inside of us. Though we had four cups and four spoons aboard, we often just split and shared meals into two cups, which made for less spills and less clean-up. No shower aboard, but hair was brushed, and teeth, ears, and bottoms were kept clean with fresh water.

On day 17 of our passage, James overlaid a weather file on the chart that made us both stop and stare. We were about 1300 nm from Cape Horn. The forecast showed a monster low pressure system was approaching us, very fast and very powerful. The diameter of the system was so wide that we had no way escaping it. Wind forecasts were no greater than what we had already experienced in the Southern Ocean. Our hope was to stay ahead of it, but we were sure to get some very strong winds and big seas. We prepared for the big blow, taking extra care to make sure that everything on board was strapped down and put away carefully.

As seas grew bigger and winds increased over the next three days, we spent most of that time hunkered down in our berths, with little activity aside from necessary sail changes and charging batteries. The boat speed combined with sea state created so much air in the water that it was difficult to use the water maker.

Outside were the largest seas I have seen since I started sailing. They were magnificent dark blue walls that rose up behind us like mountains. As they peaked and the sun shone through them, they turned crystalline blue, then broke, leaving the dark deep awash in sea of white foam. Nature had never appeared more beautiful, dangerous and powerful to me.

With four reefs in the main and a fully battened storm jib, we were in the system and had big mile-maker days, covering just over 1000 nautical miles over the course of three days. Wind speeds were between 40-50 knots, gusting 60-70. Over the course of the depression, there were 3 times when a wave caught us just right, nearly knocking us on our side before James could correct the boat.

By first light on day 21, the wind at last abated, and we felt our muscles relax for the first time in days. We were steadily moving East toward the Horn. Winds had decreased from 60-70’s back to mid 30’s and we were feeling the pressure of the last few days slowly starting to dissolve.

We were approximately 300 nm west of the Diego Ramirez Islands and excited to know that we would be around the Horn within the next day and a half. We were pointed on a course to go directly through the middle of the Drake, as far from the land as possible. It felt a little strange to be so close to Chile and Argentina, places so familiar to us, and not stop, but I knew it could not be part of the plan.

The wind had laid down, but the sea state was still large, periodically bringing a big wave that slammed hard and loud into the side of the boat. After days of being crammed together in one berth, Tormentina was stretching out, sleeping alone in the port side quarter berth. James was lying on the nav station seat, boots and bibs still on, which he hadn’t taken off in 72 hours. He had his eyes closed and was fighting a headache that was threatening to turn into a migraine, all from the intense pressure of maintaining everything during the big blow. I was in the starboard berth, watching the instruments, while Raivo and Pearl both slept.

Out of nowhere, a huge wave hit the boat, just at the right angle, pushing us on our side. “James!” I yelled, feeling the boat start to heel over dramatically as my body shifted in the berth. I was hoping he could correct the boat before we got knocked on our side.

At the sound of my voice, James reached his hand for the pilot remote. But before he could do anything, we accelerated fast to port, heeling over beyond the point of correction, approaching 90 degrees.

In slow motion, I saw James’ body lift into the air toward the port side of the boat. I felt myself getting slammed inboard and quickly braced my body to make sure I would not crush the kids. Raivo must have nudged his way to the opening of the berth in his sleep because as the boat continued heeling to port, one moment I felt his body next to mine, then immediately felt him slide out of the berth and his voice as he let out a long “Ahhhhh!”

I reached out and just missed grabbing his ankle, watching in horror as his body flew out of my reach, along the floor and past the center-line of the boat.

In the next instant, Raivo slid along the floor all the way to port , making contact with the ballast tank while James was simultaneously airbourne. Water rushed along the port-light window. As the boat continued to roll past 100 degrees, both Raivo and James both hit the cabin top. Next I saw the ocean churning on the other side of the Lexan windows at the top of the boat. I heard Tormentina yell, “Mom!” from her berth.

After that a deafening silence filled my ears. Time seemed to freeze and I felt this warm tingling feeling inside of me, expecting water to burst next into the boat or for us to fully roll 360. I thought to myself that I was so glad we had really lived it to the fullest with our kids. The last five years with them had been incredibly magical, so full of love and joy, and I felt we had experienced more with them in those few short years was more than what most people did with their children over a lifetime. I didn’t feel any regret and my last thought was that I if I could go backwards, I wouldn’t have changed a single thing.

Filled with this warm calm, everything stopped.

Water did not come rushing in, we did not roll upside down. Like magic, the boat came back up the same way she had come. James and Raivo both dropped down to the floor. My sense of hearing returned to me and I heard clanging in the galley as our cookpots rattled back into place and a few loose items dropped to the floor.

Raivo cried out, “Dad!” and James helped him up, asking him if he was okay. He angrily replied, “Yes, but I bumped my head and my back!”

“Is everyone else okay?” James asked as he looked in Raivo’s eyes and gave him a thorough head-to-toe inspection.

I looked at Pearl, who was awake now. “You alright?” I asked her. She couldn’t talk yet, but she gave me a nod.

Tormentina and I both replied, “Yes.”

James brought Raivo to me and he crawled back in the berth. I held him tightly. Then I tried to look him over myself, but he shrugged me off, and crawled down low in the berth, under the sleeping bag by my feet.

We asked Tormentina if she was sure she was okay, and she said, “Yes, but I got wet. There’s water on this side and my head got squeezed between the gray spares boxes.”

James checked on her and tucked her back into her sleeping bag.

He then stood up and held onto the grab rails, looking up through the windows of the cockpit bubble.

“Oh no,” he said. “We lost the rig, Somira.”

Everything was quiet. All we heard outside was the swirl of the ocean moving around us as we bobbed around, no longer under sail power.

“No,” I replied, in disbelief.

“Yes,” he repeated, his face awash with disappointment.

Tormentina said, “The mast is broken! What are we going to do? How are we going to sail the boat?”

James reassured her, “It’s okay, we’ll be fine. We’re going to figure out a way to get into port. Don’t worry, sweetheart.”

He was calm. Incredibly calm. Too calm.

I felt strangely calm too. It seemed like a situation like this should have put all of us in big panic. If we were in a Hollywood movie, there would be some dramatic music playing in the background or someone would be screaming or running around. But there we all were, all okay, no blood, no screaming, just present with the reality. We were on our boat, like we had been so many countless days before, and as unreal as it seemed, the mast was broken.

We knew before we set off that losing the rig was a possibility, but we had hoped that this worst-case-scenario would never happen. The kids had heard many epic stories from James’ sailing adventures before, had seen YouTube videos of boats losing their masts, and had been around enough sailors, especially in Auckland, to hear countless tales of boats getting dismasted, rolled and knocked down.

James put on his action suit quietly, meticulously checking his safety gear like normal, as if he was going out for any regular sail change.

“I need to go out and assess the situation,” he said.

“Let me know what you want me to do or if you need me to come out.” I told James.

“Okay,” he said. “I want everyone to stay put in the berths.” With that he stepped outside.

I held onto Pearl and kissed her tiny hand, who was awake and breast-feeding. I tried to talk to Raivo, but he said, “I just want to go back to sleep.”

Tormentina was the opposite, wide awake and wanted to talk, chatting away non-stop. She kept asking, “What are we going to do? I can’t believe we broke the mast. This is bad, this is really bad, isn’t it? How are we going to get to France?”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “We’re going figure out a way to get into port. Everything is going to be okay.” I took a deep breath, hoping that my promises would be fulfilled.

I looked around. A few of our duffels bags had shifted out of place. Seas were still rough & messy, and I was worried about James up there with the rig loose. I hoped more than anything that there was some way we could make a jury-rig, and that no holes were in the hull or deck. I was incredibly sad and disappointed, but the feeling of relief that everyone was okay overpowered all other emotions.

I could not image a scenario where someone was seriously hurt. Amazingly, Anasazi Girl had done what she was designed to do, her structural integrity had kept everyone safe. I thought about the way Raivo and James had moved through the short distance inside the cabin, and how even their impact had been controlled by the layout and the response of the boat.

“Let’s listen,” I said to Tormentina, “and make sure we can hear your Dad. As soon as it’s safe, we’ll get you moved over to this berth, but for now, let’s be still and quiet, because it’s still dangerous out there and we have to make sure we’re ready to help your Dad if he needs us.”

We listened to the good sounds of his footsteps and the scrape of the carabineer that kept him tethered to the boat as he moved around on deck.

When he came down below, he sat down at the nav station, looking completely defeated.

“It’s a mess out there. There are two head sails streaming in the water. The rig is in three pieces, broken at the top above the hounds and broken about a meter above the deck. That piece is lying fore & aft along the cabin-top. The boom is still attached and I’ve got that secured so it’s not banging around.”

Waves slammed against us and we heard the scrape of carbon as the mast shifted over the cabin.

“Are there any holes in the boat?” I asked.

“No, not that I can see,” he answered.

“Can we save the rig?” I asked.

“I’m going to try. I need to do something right away. With all this stuff floating in the water, we have to minimize any potential damage. We can’t risk damaging the rudders or the hull.”

He looked at the chart, marking our position on both the paper and electronic versions before turning off the electronics. We were approximately 320 miles from Cook Bay.

“If we can get ourselves to Bahia Cook, then we can anchor there until the seas lay down. Then maybe we can make a jury rig to get into Puerto Williams.” said James.

“Right now I need to focus on cleaning up. The safest thing is for everyone to stay put. Don’t walk around, don’t do anything, just stay in the berths. I don’t want anyone to get hurt.”

James took a sip of water in silence. He double-checked his safety gear and started up the companion-way steps.

“Now is the time when I have to be really smart,” he said, more to himself than me, before he opened the door.

The hours that followed were the most difficult moments of waiting I have ever experienced. The seas were terrible, and we listened to the sound of James as he worked above. I knew I had to be down below to take care of the kids, but I felt helpless and guilty for being there, dry and safe, while James was out in there risking his life. If it was quiet for too long, I would sometimes let my imagination go to negative thoughts. In this situation, it was very hard to exercise mind control to keep completely positive.

At one point, a wave hit us hard and the mast moved dramatically, scraping loudly across the deck. James gave a loud sharp yell from above.

“Are you OK?!” I yelled.

No answer.

“James!” Tormentina and I yelled again a few times. “Are you OK?”

Silence. After some time of no response, I got out of the berth and opened the door to yell out, while keeping an eye on the kids. Finally he answered with an “I’m OK.”

We were separated by the cabin-top, but in reality, he was another world away.

Every muscle in my body was knotted with tension as we waited while he continued to work. At last, he came down below.

“Are you alright?” I asked. “You really scared us when we heard you yell. I thought maybe you weren’t on the boat anymore.”

“A wave hit the boat and the mast turned 90 degrees,” he said. “I got pinned against the stanchion and life lines,” he explained. “I thought that was going to be it for me.”

“Did you get hurt?”

“Yes, my back, the spot where I got pressed against the stanchion,” he said. “But I got the solent cut away and the got rid of the broken top piece of the mast. The storm jib is gone, but I managed to save the trinquette. I need to cut the rig away – I think that it’s too messy out here and too dangerous to try to keep it on the boat.”

James went back out and worked the following hours to cut the mast away. We could hear him grunting in effort as he worked to lift and move the sails and mast. I was sure that he was running purely on adrenaline at this point because he had hardly had any sleep, food, or water.

Once it was safe for us to move around the cabin, I helped Tormentina get into dry clothes, use the toilet, and eat some food. She was now in my berth, warm and dry, watching a movie with Pearl. Raivo was asleep.

About six hours after the mast first broke, James finally stopped working. He came inside, took his gloves, harness, and jacket off.

He sat down at the navigation station and looked absolutely and completely hammered.

The mast was now gone, at the bottom of the deep blue. So was one head sail, a storm jib, some lines and some hardware. Part of the main that was saved was lying on the side deck. Some of our sheet bags were missing, the mesh at the back of the transom, and a couple of winch handles had disappeared. The water that had come into Tormentina’s quarter berth was from the ballast tank. An air vent pipe coming from that tank had gotten cracked by one of our spares boxes getting shifted around. With us being on our side, saltwater had flowed up back through this pipe.

We did not speak. I offered James some hot soup and water. He ate a little bit, but it was obvious his appetite was completely gone. He laid across the navigation seat, and closed his eyes in complete exhaustion.

While he slept, I stepped out in the cockpit for the first time since we were knocked down. The sun was shining, the horizon was filled with blue skies and a few gentle looking white clouds. Seas were still uncomfortable, but nothing like the monster waves that had been slamming into us.

It was as if the storm had never happened.

However, staring forward at the stump of the mast sticking out of the boat brought me back to reality. James had thrown part of the main over it, and the boat was sailing on course at 3-4 knots with the autopilot and no rig.

I went back down below, still blown away that we had actually lost our rig. While everyone rested, I started to organize things down below, putting loose items away, cleaning, drying the floors, making food. I washed my face and brushed my teeth. These simple things helped make things feel somewhat “normal”.

When James woke up, it was approximately 8 hours after our knock-down. We had lost our Sea-Me and radar units. Fortunately the antennas and comms units mounted on the transom were still intact. James and I re-worked our NMEA interfacing so it would work with the Sea-Me and radar components gone from the hub. Once it was reconfigured, we fired up our system and our instrument data was once again working with our navigation software. We calculated time, distance, and fuel needed to get to Cook Bay. Based on our calculations, if we motored full power at 6 knots, we could get in within 50-60 hours. We were approximately 50L of fuel short for this distance. This was not taking into consideration opposing factors like currents, wind on our beam, or drift.

We had a choice, let ourselves drift toward Cape Horn and then motor to the Beagle, or we could start to motor now to Bahia Cook.

We did not immediately call anyone. We knew if a rescue was initiated, it was not only a sure-fire way to lose Anasazi Girl, but it would also mean expense & risking the lives of other people.

The boom was designed to stand up. We decided our best chance was to motor to Bahia Cook and then make this jury rig at anchor.

James started the engine and pointed us on course for Bahia Cook. All unnecessary electronics and the heat were turned off, and we all bundled up.

As we motored and watched our fuel drop, we slowly came to terms with the fact that were not going to make it in without help. We reluctantly made a call on the SAT phone to the Port Captain’s office in Puerto Williams to inform them of our situation to see if we could hire a nearby fishing boat to meet us close to Bahia Cook to do a fuel drop. We had filed their number as part of our pre-voyage planning.

In Spanish, James explained to them that we had lost our mast and were approximately 50L short fuel to get into Cook Bay. He gave them his full name, our boat name, position, our MMSI number, last port of call, the number of crew members aboard, and our SAT phone number. He informed them that no one was hurt on board. He told them there was no immediate emergency. James asked them if there were any nearby vessels we could hire to meet us with fuel. They said they would be in contact with us.

That was it. The call was made, and felt somewhat anti-climactic. After a few hours had passed, we were unsure if they fully understood our situation.

We called our close friend Andy Ball in New Zealand, who had been there in Auckland to untie our lines at the dock. We updated him on the recent events, James telling him that he thought maybe he had cracked one of his ribs cutting the rig away. We then emailed him details of our position, asking if he could contact New Zealand Coast Guard to assist us with communications with Puerto Williams as we were unsure whether or not they understood.

We also called our friend Richard Duffau, a French sailor who had spent a number of years cruising in Chile, and had spent some years in and out of Puerto Williams. He told us to continue heading for the coast and assured us that if the Armada de Chile were involved, we had nothing to worry about, that they would make sure we got in safely.

We spent a very sleepless night aboard Anasazi Girl. Very early the next morning, we made a second call to the Port Captain’s office in Puerto Williams, updating them with our position, and assuring them of the status of everyone’s health aboard. New Zealand Maritime had been in contact with them.

James asked if they would be able to provide us with any fuel. They told us that they would not be dropping us any fuel. They said a rescue had been initiated to pick us up and that the closest merchant vessel had been diverted to our last known position. We needed to contact them every hour on the Iridium with updates on our position.

After this call, James looked at me in pure defeat.

“Somira, they’re not giving us fuel. The Navy launched a rescue.” He then relayed the other half of the conversation.

We couldn’t believe we had gotten this far, and that in an instant, our fate had been altered.

We had suddenly done what we never wished to do, and that was get other people involved and risking their lives to help us. Our life program was about to change very dramatically. If they were sending a container ship, then we did not know how we could possibly do a safe transfer or how in these seas they could come up alongside us, or how they were going to safely lift us and our children such a big height without someone getting hurt. The risk in this situation for us was very high.

James and I wanted to call the Armada and deny a rescue, but felt conflicted because we had our children aboard. If it was just the two of us it was another story. After some time talking, we agreed that getting picked up meant a better guarantee of safety and continued life for our family, even at the higher risk of possibly getting hurt in a transfer. We couldn’t let our egos overshadow the most important thing, and that was the safety of our children.

Over the next two hours, we contacted the Armada with our position, and continued on our course to Cook Bay. When the kids woke up, we told them that the Chilean Navy was going to help us, that they were sending a ship for us to bring us to port. We also told them that this also meant we were going to say goodbye to Anasazi Girl.

This was very emotional and tearful news for our two oldest, especially Tormentina. The boat had become, over the last three years, their home. Considering their short lives, this was like forever in their minds. We explained that there was a possibility that James could stay aboard and try to get the boat into port himself, but really the Armada was in charge now, and we had to do what they said. The biggest thing was that we would all be safe.

Tormentina said that James staying with the boat wasn’t an option, that we were sticking together like glue, even if it meant losing Anasazi Girl.

James told her that if that was what she wanted, then “sticking together” what was we would do.

Then he asked her what she wanted to do next, that it was just a boat. We were together and we could go anywhere and start a new life.

She replied, “I want to go to live somewhere warm, where I can wear a grass skirt and swim in the water every day.”

We laughed, and said that we would not need to pack very much then.

James prepared the Anasazi Girl for the rescue, clearing everything from the deck. We did not know what side the ship would come alongside us, and figured the best thing to do was to keep everything as clean as possible to guarantee everyone’s safety.

After very difficult comms for the last three calls over very patchy Iridium coverage, we got a call from the Port Captain’s office in Puerto Williams that was crystal clear.

The man on the phone spoke perfect English and said that his name was Captain Juan Soto.

James updated him our position and our current course. James explained to Juan that we were conserving fuel so that we could stay on course and get as close as possible to Cook Bay. He told Juan that he was really worried about how we could safely get picked up by a container carrier.

Juan Soto said, “James, don’t worry. The merchant ship is the stand-by vessel now. I am leaving Puerto Williams right now with my ship and my men, and we’re coming to get you. Please eat, drink water, rest, and turn the heat on.”

James felt instantly at ease after this call. The pain in his back had settled in. When he used the head that morning, he came back saying he was urinating blood. For him, the adrenaline hard worn off and the reality of his physical condition set in, making him realize that trying to get in without help really wasn’t an option.

We turned the heat on, and the warmth made the boat feel like home again. We continued making calls with our position report, the connection on the SAT phone was poor, making this simple task difficult.

At one point the Armada informed us that a special Navy plane would be flying overhead that could see submarines in order to make a visual confirmation of our position. Our vessel, being carbon, presented a very small radar signal, and they were concerned about losing us if our communications suddenly failed.

Shortly after, we heard and saw the plane overhead, and James talked to the pilots on the plane on the VHF radio.

True to his word, Commandante Soto was the first to arrive on the scene with his ship PSG-78 Piloto Sibbald, crewed by 28 men. The plan was to rendezvous with us at first light.

After two nights on our dismasted vessel, we heard and saw the Navy plane fly overhead a second time. We saw the Sibbald in the distance approaching us, and the merchant vessel standing off.

In big seas, two zodiacs were launched by the Sibbald, one of which tied up alongside us. In the zodiac were two crewman, two rescue divers in wetsuits, a medic, and a young officer who spoke perfect English.

When asked about our health, James told the officer, Lieutenant Javier Germain, that he thought he had cracked a rib, was pissing blood and very much in pain now.

Javier asked permission to come aboard, which we gladly gave. Javier squatted on the starboard side deck and said that we would get transferred first by zodiac, checked over by the medics, then the Commandante would talk to us about what would happen with our boat. He asked if we were ready to do this, and we answered, “Yes.”

I put a hand on Anasazi Girl one last time and said a silent goodbye to her as I stepped off her for the last time, holding back tears. We all watched with heavy hearts as we drove further away from the boat in toward the Sibbald, the saltwater spraying us as we made our way through the seas. In a big swell we were able to tie up alongside the Navy ship after two attempts.

We had prepared the kids for the pickup ahead of time, wearing their helmets and PFD life vests with built-in harnesses with a carbineer hanging and ready to clip. This was perfect, because once we were alongside the Sibbald, we were easily able to clip them safely into a line and they got lifted up quickly and securely. Pearl was lifted first. I climbed up the ladder second after I told Tormentina and Raivo to be brave, that I would see them in just a few moments. Once I was aboard, I was greeted by smiling crew members, who handed Pearl to me immediately.

I was ushered inside while the other two kids were getting lifted and soon they were reunited with me. James was lifted aboard last by a crane, clipped in with the rescue diver. We were all brought into the infirmary, where there were four bunks and an examination table. I removed all the kids’ safety gear and jackets. There were two medics there who checked our vitals and asked us questions.

After this, Commandante Soto came into the infirmary and welcomed us aboard, speaking perfect English.

He was a tall, fit man in his 40’s, with curly salt & pepper hair. We both shook his hand tightly, and thanked him for risking his life and his men’s to save us.

James explained to the Commandante in Spanish that when he heard his voice over the SAT phone the day before, he felt instantly at ease about everything.

In that instant of coming face to face with him, we felt an irreversible connection and lifelong friendship solidify between us.

Juan Soto said he had four children, the youngest three were the same age as our children. He also explained that most of his crew members also had children, and that they were all really happy that we were safe.

The looks in everyone’s eyes aboard said it all. This was a life changing moment for all of us involved as we came together in this incredible instant.

Juan told us that he believed there was just enough of a weather window that he thought he could tow Anasazi Girl in. He said he would be willing to put a line on her and would she be okay towed at 15 knots? If for some reason there was a problem that would create a risk for their vessel or they couldn’t make sufficient speed, then they would have to cut the line.

James and I were shocked. We had fully expected the discussion to be about opening her through holes to sink her, not at all this scenario. Rescues were about saving lives, not things, and we had already let go of the boat.

We agreed to sign a release for them to do this. Lieutenant Germain talked to James about the best way it should be done, then returned with the same divers and crew-men who had been in zodiac that picked us up to tie a tow line to the boat.

Hours later, we quickly underway toward Bahia Cook. James was lying in a berth in the sick bay, finally physically finished after this epic and very difficult trial of the sea. He was certain he had broken one or two ribs. He was now fully dehydrated, on pain meds and an IV.

I felt as though we were in a dream. Maybe we had really died, and this was some post-life fantasy being lived out. Or maybe I was still stuck in that moment before water was about to rush inside the boat. I had to pinch myself, as my kids and I stood on the aft deck of the Navy ship, watching our dismasted sailboat getting towed behind us just beyond the ship’s wake.

We were all safe, with James suffering minor injuries. As if by letting the boat go, she was somehow miraculously returned to us. We were together and Anasazi Girl was coming home with us.

To stay up on the Burwick family‘s adventures and Anasazi Girl visit the Anasazi Racing blog Here